February 3, 2007

Cuisine: French

1523 Walnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19102

Phone: 215-567-1000

Website: http://lebecfin.com/

–

I usually find writing restaurant reviews effortless, but am having the most difficult time translating my Le Bec Fin experience into words. So rather than writing a traditional evaluation piece about the food and mood, telling a story about the entire evening seems more appropriate for this occasion.

Le Bec Fin, which means “fine palate,” opened in 1970 and is undoubtedly Philadelphia’s finest restaurant. Le Bec Fin has received the highest accolades in the hospitality industry and has been a long-standing recipient of both the coveted Mobil Five Star and AAA’s Five Diamond awards. At $138 per person for the six-course dinner and $165 for the ten course dégustation, this is not your everyday eatery. I asked one of the waiters about Le Bec Fin’s clientele and was informed that most diners are special occasion eaters rather than regulars.

Our special occasion for visiting Le Bec Fin was my 25th birthday. The Astronomer spilled the beans back in December that he had made a reservation to celebrate me living for a quarter century after I had posed the question, “Are we ever going to eat at Le Bec Fin?” Needless to say, I have been anticipating this dinner for months.

The restaurant has two seatings on Saturday evenings; one at 6 and another at 9:30. There is a doorbell outside the restaurant we were hoping to ring because we have walked by it countless times on Walnut Street, but the door was already unlocked. We arrived fashionably late for the 9:30 seating and were brought into the main dining room after we checked our coats, scarves, ear muffs, and mittens.

Our table was candlelit and situated between two other couples. Most diners seemed to be in groups of two or four; there was one larger party of ten or so just outside the main dining room. Le Bec-Fin underwent major interior renovations in the summer of 2002 transforming their dining room into the late 19th century elegance of a Parisian dining salon. The main dining room fits only fifteen tables and feels comfortable, warm, and intimate. Waiters pulled out our chairs and fluffed our napkins as we took our seats.

The Astronomer and I decided to go for the six-course dinner so that we could choose our delights and thus try more of Le Bec Fin’s offerings. The ten-course dégustation is pre-set and contains the chef’s signature dishes throughout his career. After we made our menu selections we were brought bread and butter. I chose the multi-grain roll, while the Astronomer chose the sourdough. The Astronomer thought that the bread was too crusty. The butter was rich and spread nicely on my roll. Soon after we were brought an amuse bouche of scallop mousse with pomegranate.

Amuse Bouche

Scallop mousse with pomegranate

I ate my scallop mousse in one swift bite, while the Astronomer had his in several. The mousse was light in my mouth and airy in texture. The pomegranate seeds unleashed a divine tartness. The amuse bouche certainly excited our taste-buds for the courses to come.

All of Le Bec Fin’s appetizers sounded delectable and we had a truly difficult time choosing. I was strongly leaning toward one of the evening’s special appetizers which was layers of smoked salmon with cream cheese, but settled on Le Bec Fin’s famous crab cake instead. I figured I could return to Brasserie Perrier for the same smoked salmon. The Astronomer chose the escargot.

Les Entrées

Cassolette d’escargots aux noisettes en hommage à Monsieur Cleuvenot

Cassolette of snails in a Champagne and hazelnut garlic butter sauce

Galette de crabe aux haricots verts

Our own crab cake, a signature dish

The Astronomer wished that the escargot were served in their shells as they are in France, but enjoyed them nevertheless. The escargot were cooked in a luxurious garlic, cream, and butter sauce. The hazelnuts were surprisingly mild in flavor, but added a lovely crunch. Although he knew it was bad for his health, the Astronomer devoured every last drop of the rich sauce.

The crab cake was insanely delicious and decadent. It was full of jumbo lumps of crab and shrimp and dressed in a whole grain mustard sauce. Every bite tasted like heaven. The hericot verts and tomatos helped cut the velvety sauce and balance the flavors beautifully. A signature dish indeed.

Our second course was fish. I chose the grouper because the flavor combinations sounded quite unorthodox, especially for a classic French restaurant, while the Astronomer went for the halibut.

Les Poissons

Filet de mérou en croûte de noix et abricots secs, Bolognaise de tomates et palourdes, sauce au persil et wasabi

Crusted grouper with dried apricots and nuts, tomato Bolognese with clams, parsley and wasabi sauce

Flétan roulé au bacon, brocoli amer et sauce à la truffe

Halibut wrapped in bacon, broccoli rabe and truffle sauce

The grouper was fabulous. The crust was perfect and did not over power the fish’s natural flavor. Although I could not taste the apricot, the nuts came through nicely within the crust. The clam Bolognese was skillfully prepared and paired nicely with the heartily crusted grouper. The sauce was definitely more parsley than wasabi and thus extremely mild; the wasabi was sadly muted.

I only had a single bite of the Astronomer’s halibut because I was enamored with my own fish. He was nervous about ordering a dish containing truffles because he is not a fan of mushrooms, but was pleased to find only a subtle truffle flavor. The bacon added a lot of flavor to the delicate fish.

I was getting very stuffed after I finished my fish, which was not good because we still had four more courses to go. For our meat course I elected to have the rabbit because I had never tasted rabbit before. The Astronomer went for the lamb because it is one of his favorite meats.

Les Viandes

Selle de lapin farcie aux épinards et champignons, cuisse braisée en chou vert, compote de choux rouges jus de lapin aromatisé à la sauge

Rabbit saddle stuffed with spinach and mushroom, braised leg wrapped in green cabbage, red cabbage compote rabbit jus flavored with sage

Carré d’agneau, panisse poêlée et petit bok-choy, jus naturel

Domestic rack of lamb, crispy chickpeas and baby bok-choy, natural jus

I thought rabbit tasted a lot like chicken only lighter in flavor. The skin was especially delicious. The spinach and mushroom stuffing was mildly flavorful and could have used some more pizazz. The red cabbage compote was a simple, yet elegant side. The green cabbage with the rabbit confit was good as well, but I was too full to enjoy it. The Astronomer ate most of my dish.

The Astronomer’s lamb was carved table-side and cooked medium-rare. It was the best lamb I have ever eaten. The meat was juicy and lusciously earthy. Even though my stomach was ready to stop, I made room for the lamb because it was insanely scrumptious.

A cheese course followed our meat course, which was an interesting change of pace. This was my first cheese course so I was excited to see how my taste-buds would react to eating cheese post-dinner rather than pre-dinner.

Les PÂTURAGES

Fromages frais et affinés par nos soins

Our selection of fresh and aged cheeses

The selection of cheeses on the cheese cart was phenomenal. With so much variety we did not know where to start so we asked the resident cheese expert to serve us a range of creamy, mild, sharp, and hard cheeses. My favorite was the Gouda; it was sharp, salty, hard, and perfect. My second favorite was the Bleu; it was the mildest Bleu cheese I had ever tasted. Since I had never tasted Camembert, the Astronomer warned me that it was extremely stinky. I enjoyed the Camembert’s unique taste and creamy texture. I love how the flavor stayed with me long after the cheese was gone.

To transition from savory delights to sweet ones, we had a course of sorbets to cleanse our palettes. There were two flavors to choose from: coconut and pear. I chose the coconut because pear is the Astronomer’s favorite fruit.

Sorbets (Coconut, Pear), glaces et Desserts du Bec Fin

The coconut sorbet was a refreshing change after eating so many rich foods. The coconut flavor leaned toward processed rather than fresh, but in a good way; fresh coconut probably would have been too delicate. The pear sorbet was far sweeter than the coconut and the Astronomer surprisingly liked the coconut more. I think the pear sorbet was made of canned or preserved pears due to its texture and syrupiness. Our sorbets were served in funky blooming bowls that made eating the melted sorbet impossible.

Our final course was the infamous dessert cart. As the cart rolled toward our table, a vast space opened up in my stomach! It was a welcomed miracle.

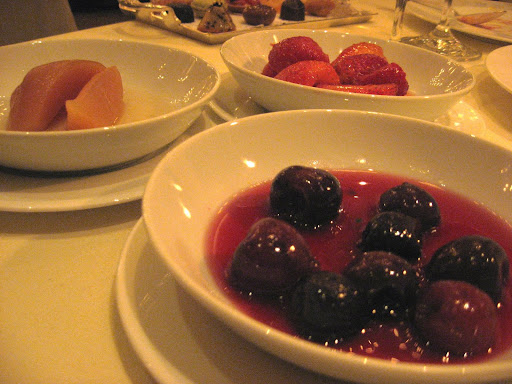

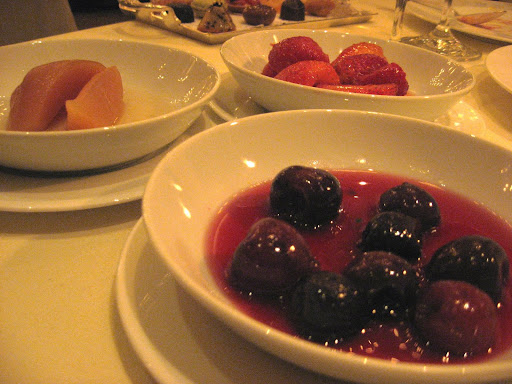

La Charrette de Desserts

A selection of tarts and cakes (top), Fruits poached in wine and vanilla (left), Chocolate and hazelnut cake (right)

The selection of treats was obscene and yet beautiful to behold. I asked the dessert specialist for a piece of every non-chocolate cake and tart. Our sampler included a lemon curd tart, Philadelphia cheesecake, coffeecake, strawberry cake and a few others whose names have slipped. I also requested a piece of the chocolate opera cake with 24k gold leaf, a selection of poached fruits, and the Grand Marnier soufflé.

The Astronomer and I both loved the cheesecake and the red wine poached strawberries. The opera cake was soaked in rum and a bit too strong for our palettes. The Grand Marnier soufflé was out of this world creamy; we ate every last bit.

Lastly, I requested a piece of the chocolate and hazelnut cakes. There are two versions of this cake; one where the meringue becomes sponge-like during the baking process and another where the meringue becomes cookie-like. I did not care much for the sponge version, but I adored the cookie version. The crunch brought about a wonderful contrast. Even though I was about to burst, I manage to eat the entire piece. Hazelnut and chocolate may be the best dessert combination ever.

Chocolats, mignardises et petits fours

Our petits fours were packed up to go because the Astronomer and I were completely stuffed. We enjoyed them all thoroughly the next day. I especially loved the macarons, fruit tart, chocolates, eclair, and chocolate chip pyramid.

My birthday dinner at Le Bec Fin was an incredible dining experience. I knew the food would be outstanding, but I did not expect to have so much fun. Fancy restaurants tend to be snooty and intimidating, but that was not the case at Le Bec Fin. The service was impeccable and the waiters were amazingly down to earth and helpful; I was at ease from the moment I stepped into the restaurant. Our three hour feast seemed to pass by in a heartbeat.